Technical Aikido

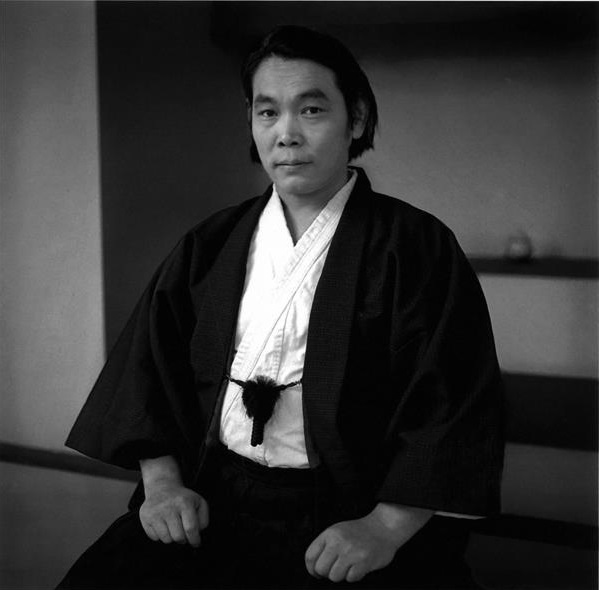

By Mitsunari Kanai, 8th Dan, Shihan

Chief Instructor of New England Aikikai (1966-2004)

Chapter 1 – Training Methods

One of the most basic, chronic, and perhaps inevitable problems in practicing AIKIDO, is that AIKIDO training can be reduced to an easy going exercise based on excessive compromise between the practice partners (NAGE and UKE). This problem arises because AIKIDO practitioners often base their practice on sincere but ill-founded philosophies and theories.

Examples of the many incorrect interpretations of AIKIDO as applied to practice include emphasizing an idea of an “AIKIDO style” ambiance, expressing an “ideology” of AIKIDO, and misconstruing the concept of “harmony”. Because of the importance of correctly understanding the meaning of harmony in the specific context of AIKIDO, I will give a brief explanation. Keep in mind that I will cover only a tiny fraction of the meanings and aspects of AIKIDO’s harmony.

First, it is important to know that harmony is a central component of AIKIDO. Most fundamentally, it means harmony with the entire universe, with all existence. In terms of mind and body, harmony simply means that one should equally emphasize each, rather than focusing on one or the other. But in physical terms, harmony has a technical meaning referring to a certain way of using one’s entire body in every movement.

Applied to a confrontational situation (including training), it is this technical meaning of harmony one must realize in oneself and with the opponent, and create a situation that brings the opponent into harmony with oneself. Harmony does not mean just getting along with people on the basis of a lowest common denominator, or creating agreement without regard to rules in order to avoid confrontation and maintain an easy going or overly comfortable environment.

Harmony, as used in AIKIDO, does not involve compromising, diminishing, or diluting opposing things and their individual essences. Such an approach waters everything down, sacrifices the essence of things, erodes standards of behavior and attitude and thereby diminishes each individual. Rather, AIKIDO’s harmony brings different — even opposing — elements together and intensifies them in a way that drives everything toward a higher level.

It is often pointed out that AIKIDO permits men and women, adults and children, and old and young to practice together. This is true.

It is equally true, but not as frequently noted, that within AIKIDO there is also room to practice in other ways, for example, to use very hard practice to develop martial techniques.

AIKIDO’s breadth and inclusiveness does not mean that its practice is easy, or that those practitioners focusing on developing hard fighting techniques are less important, or less legitimate, than those interested in other of its aspects.

The result of these errors, I suspect, gives rise to the first major problem in AIKIDO training, which is that many AIKIDO practitioners have been unable to establish a training method based

on the most fundamental understanding of how to use the body to produce, apply and receive power. What follows is a theory and explanation of how to correctly use the body. It seems to me necessary to articulate in detail this logic of AIKIDO. It is intended that this articulation of AIKIDO’s physical principles should replace the abstract explanations typically advanced by many practitioners of AIKIDO and other martial arts.

The AIKIDO practitioner must understand how the physiology of the body, the very structure of the body, gives rise to rules or principles of how the entire body should most efficiently and optimally function. Correctness of a body movement is judged solely by this criteria: whether the movement, in light of human physiology, utilizes with complete economy all the parts of the body organized in the most efficient possible way. Understanding such a fundamental theory of body utilization must precede explanations of the specific techniques of AIKIDO. Any system of body movement must be based on human physiology.

The martial arts in general have rules which further define the implications of the human physical structure in the context of combat situations. AIKIDO, which is aimed at the broadest approach to martial arts, should have an even more precise set of principles. A specific technique based on these principles will utilize every part of the body, organized and sequenced so as to optimize the generation of power. If this is done, the technique will be correct and will “work”. Failure to understand and apply it makes techniques ineffective.

One must understand that AIKIDO training should be solely based on this uncompromisable principle of maximum efficiency arising from human physiology. Armed with this understanding, the practitioner may readily determine whether techniques that may look free flowing and correct are based upon the true principles of AIKIDO training.

Incorrect techniques are all too common due to failure to understand this principle. The failure to understand the principle of efficient body movement has other implications, for example, that the main groups of techniques characteristic of AIKIDO (throws, holds, strikes, and thrusts) lack a theoretical consistency and therefore appear overly distinct from each other. It should be understood that I am not proposing to constrain AIKIDO in a rigid mold but, on the contrary, I am suggesting that it is necessary to break out of a rigid mold already in existence, a mold made up of formalized bad habits. The results of these bad habits are easily observable in much of what is today called AIKIDO practice.